Summary: This paper illustrates the central role of persistence in estimating and interpreting value-added models of learning. Using data from Pakistani public and private schools, we apply dynamic panel methods that address three key empirical challenges: imperfect persistence, unobserved heterogeneity, and measurement error. Our estimates suggest that only one-fifth to one-half of learning persists between grades and that private schools increase average achievement by 0.25 standard deviations each year. In contrast, value-added models that assume perfect persistence yield severely downward estimates of the private school effect. Models that ignore unobserved heterogeneity or measurement error produce biased estimates of persistence.

Tahir Andrabi

Jishnu Das

Asim Khwaja

Tristan Zajonc

Do Value-Added Estimates Add Value? Accounting for Learning Dynamics

Citation: Andrabi, Tahir, Jishnu Das, Asim Ijaz Khwaja, and Tristan Zajonc. 2011. "Do Value-Added Estimates Add Value? Accounting for Learning Dynamics." American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3 (3): 29-54.

Models of learning often assume that a child’s achievement persists between grades—what a child learns today largely stays with her tomorrow. Yet recent research suggests that treatment effects measured by test scores fade rapidly, both in randomized interventions and observational studies. Low persistence may in fact be the norm rather than the exception. It appears to be a central feature of learning.

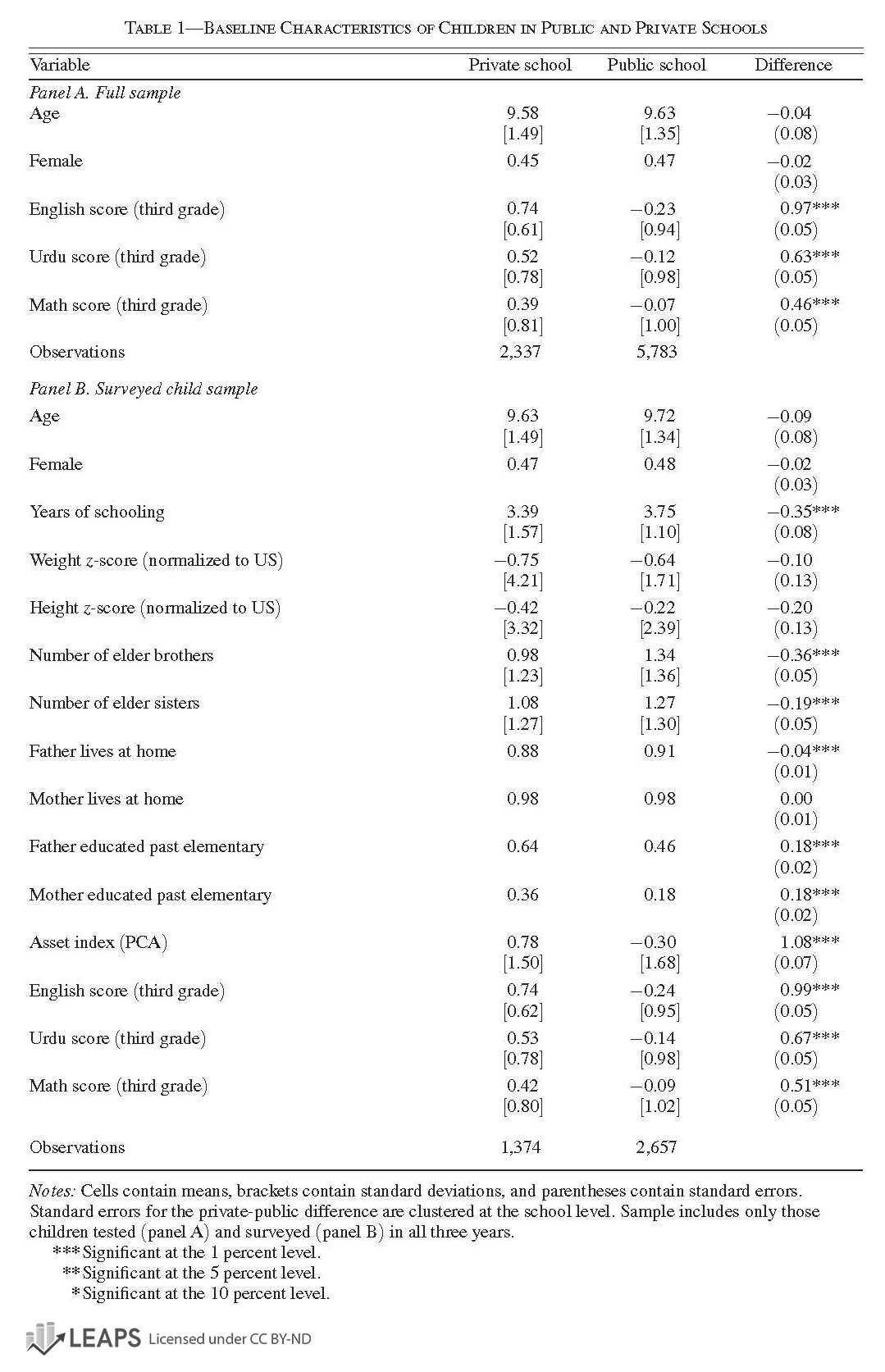

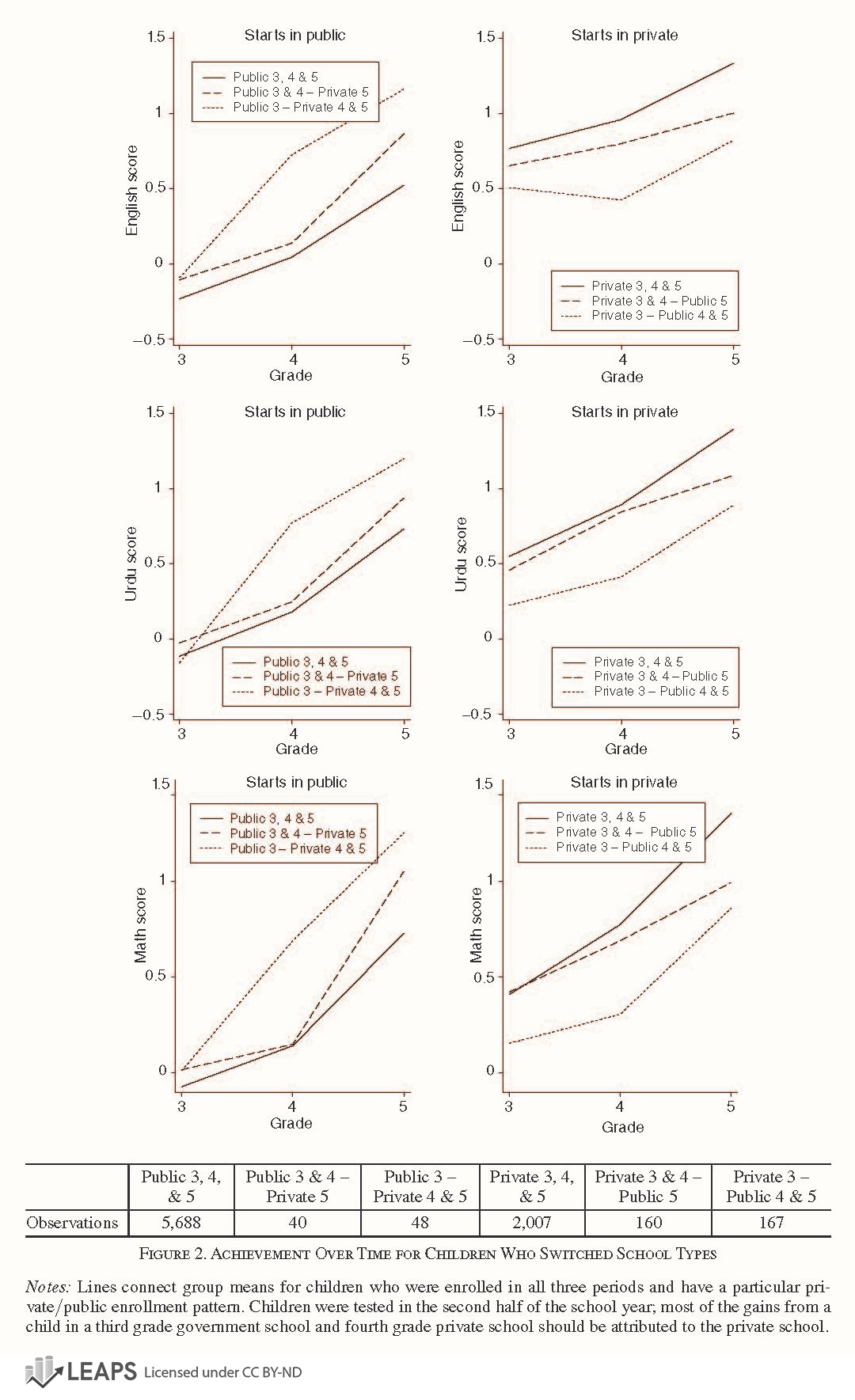

Low persistence has critical implications for commonly used program evaluation strategies that rest heavily on assumptions about or estimation of persistence. Using primary data on public and private schools in Pakistan, this paper addresses the challenges to value-added evaluation strategies posed by imperfect persistence of achievement, heterogeneity in learning, and measurement error in test scores. We find that ignoring any of these learning dynamics biases estimates of persistence and can dramatically affect estimates of the value-added of private schools.

Study Design and Findings

We use three years of data on a panel of children along with techniques from the dynamic panel literature. We find that learning persistence is low; only one-fifth to one-half of achievement persists between grades. These estimates are remarkably similar to those obtained in the United States. The low persistence we find implies that long-run extrapolations from short-run impacts are fraught with danger. If a researcher were to mistakenly assume perfect persistence, their estimates for long-run impacts of continued treatment would be much too large.

Learning persistence is low

OLS estimates of learning persistence are contaminated

OLS estimates of learning persistence are contaminated both by measurement error in test scores and unobserved student-level heterogeneity in learning. Ignoring both biases leads to higher persistence estimates. In our data, the upward bias on persistence from omitted heterogeneity outweighs measurement error attenuation.

The private schooling effect is highly sensitive to the persistence parameter

Since private schooling is a school input that is continually applied and leads to a large baseline gap in achievement, this is expected. We find that incorrectly assuming perfect persistence significantly understates and occasionally yields the wrong sign for private schools’ impact on achievement. Our dynamic panel estimates suggest large and significant contributions ranging from 0.19 to 0.32 standard deviations a year. From a public finance point of view, these different estimates matter particularly since per pupil expenditures are lower in private schools relative to public schools. Our results are consistent with growing evidence that relatively inexpensive, mainstream, private schools hold potential in the developing country context.

In the absence of randomized studies, the value-added approach to estimating education production functions has gained momentum as a valid methodology for removing unobserved individual heterogeneity in assessing the contribution of specific programs or in understanding the contribution of school-level factors for learning. In such models, assumptions about learning persistence and unobserved heterogeneity play central roles. Our results reject both the assumption of perfect persistence required for the restricted value-added model and of no-learning heterogeneity required for the lagged value-added model. Our estimates of low persistence are consistent with recent work on teacher effects and with experimental evidence of program fadeout in developing and developed countries. These results illustrate the danger of incorrectly modeling or estimating education production functions; the restricted value-added model is fundamentally misspecified and can even yield wrong-signed estimates of a program’s impact. Underscoring the potential of affordable, mainstream private schools in developing countries, we find that Pakistan’s private schools contribute roughly 0.25 standard deviations more to achievement each year than government schools, an effect greater than the average yearly gain between third and fourth grade.

Study Resources

The following resources are for public use in presentations, papers, lectures, and more under the Creative Commons license BY-ND. Click the images below to view or download individual images, or use the button to download all.

As a condition of use, please cite as: Andrabi, Tahir, Jishnu Das, Asim Ijaz Khwaja, and Tristan Zajonc. 2011. "Do Value-Added Estimates Add Value? Accounting for Learning Dynamics." American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3 (3): 29-54.