TARGETED INSTRUCTION IN PAKISTAN (TIP)

Countries around the world are facing a learning crisis. After multiple years of COVID-19-related school closures, average learning levels are low and learning inequality is high. Delivering the standard curriculum is unlikely to address either of these challenges. One of the most promising solutions to this crisis is through targeted instruction (TI), where content is tailored to children’s actual learning levels rather than their age or grade.

A large-scale pilot is currently underway to evaluate the program in two districts in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP): Peshawar and Mardan. The program aims to get all students caught up to grade level so they can continue their learning journey under the regular curriculum. To help with program administration, the pilot introduces a novel smartphone app for teachers and explores whether technology can better enable teachers to implement remedial education at scale. We have designed a series of RCTs to ask: should the system mandate the use of technology, or should teachers have the choice of self-selecting into it? How might we best leverage technology to maximize program impact?

Summary

We designed an 8-week remedial TI program to fill in students’ learning gaps, while removing frictions in teachers’ adoption of pedagogical innovation. Traditional TI is costly and difficult to implement, so we introduce a novel smartphone app for teachers with teaching material and digital classroom operations tools. Technology in this setting reduces teachers’ administrative burden and presents a low-cost alternative to adding personnel, making TI possible to scale in under-resourced countries where it is likely most needed. The software will be randomized across 1,000 primary-level public schools across Pakistan. Treatment arms vary whether:

Teachers are required to use the software throughout the program;

They are given a choice between the software or paper materials after a mandatory trial period,

They are given a choice between the software or paper materials at the get-go; or

They are or not offered the software at all (control).

This will allow us to learn about whether systems should mandate the use of technology or whether people should self-select into it. Given considerable heterogeneity in teachers’ demographics, beliefs towards pedagogy, and confidence in using technology, we also evaluate any mediating effects from teachers’ heterogeneous traits on program outcomes.

-

Can low-cost, simple technology help teachers implement remedial education at scale?

Should systems mandate the use of tech, or allow people to self-select into using it?

Is there heterogeneity in the net benefit of technology, such that it hurts some and helps others?

Do the perceptions of technology benefits change with experience?

How can we leverage group chats to build community and improve program outcomes?

-

A large majority (86%) of teachers believe their students are currently far behind the curriculum and need help catching up.

More than half of students from every class and subject combination showed need for remediation in foundational skills. In some cases, more than 90% of students in a class showed need for remediation in a certain subject.

At the end of their time in primary school, 46% of class 5 students cannot write simple Urdu sentences and 79% cannot write simple English sentences. 19% cannot do addition with carrying, and 75% cannot do subtraction with borrowing.

Note: program impacts on student test scores and teacher behavior are pending pilot completion.

A Systems View: Empowering Teachers, Removing Frictions

Using a systems-based approach, TIP identifies and addresses frictions and constraints in teachers’ adoption of pedagogical innovation:

Friction 1 - Extra workload TIP requires after-school instruction or extra teaching, and grading exams and sorting students is time consuming

TIP Solution 1: Make TIP part of regular class time; suspend regular instruction for the eight weeks of TIP.

TIP Solution 2: Teacher’s Tech Tool does automatic sorting, and quizzes are provided as well as curricular aids and lesson plans and workbooks.

Friction 2 - Excessive regulatory oversight and misaligned incentives

TIP Solution 1: Alignment of message and policy – notification from Secretary to District Office to Circle AEO to “not monitor and insist on finishing of curriculum by a certain date”.

TIP Solution 2: Training and relationship building at Circle AEO Level.

A Way Forward: Technology-Enabled Targeted Instruction

Our research team designed a contextualized, systematic approach to fill in learning gaps in foundational skills.

The Targeted Instruction Program (TIP):

Assesses every student’s actual learning level

Sorts students into appropriate peer learning groups

Uses technology to aid teachers in delivering targeted content

Study Design and Sampling

1,250 primary schools in TIP’s KP sample were randomly selected and assigned to one of five treatment arms, varying across teachers’ usage of TIP’s technology tool. Key measurables include child learning outcomes, mastery of foundational skills, and teacher take-up of technology.

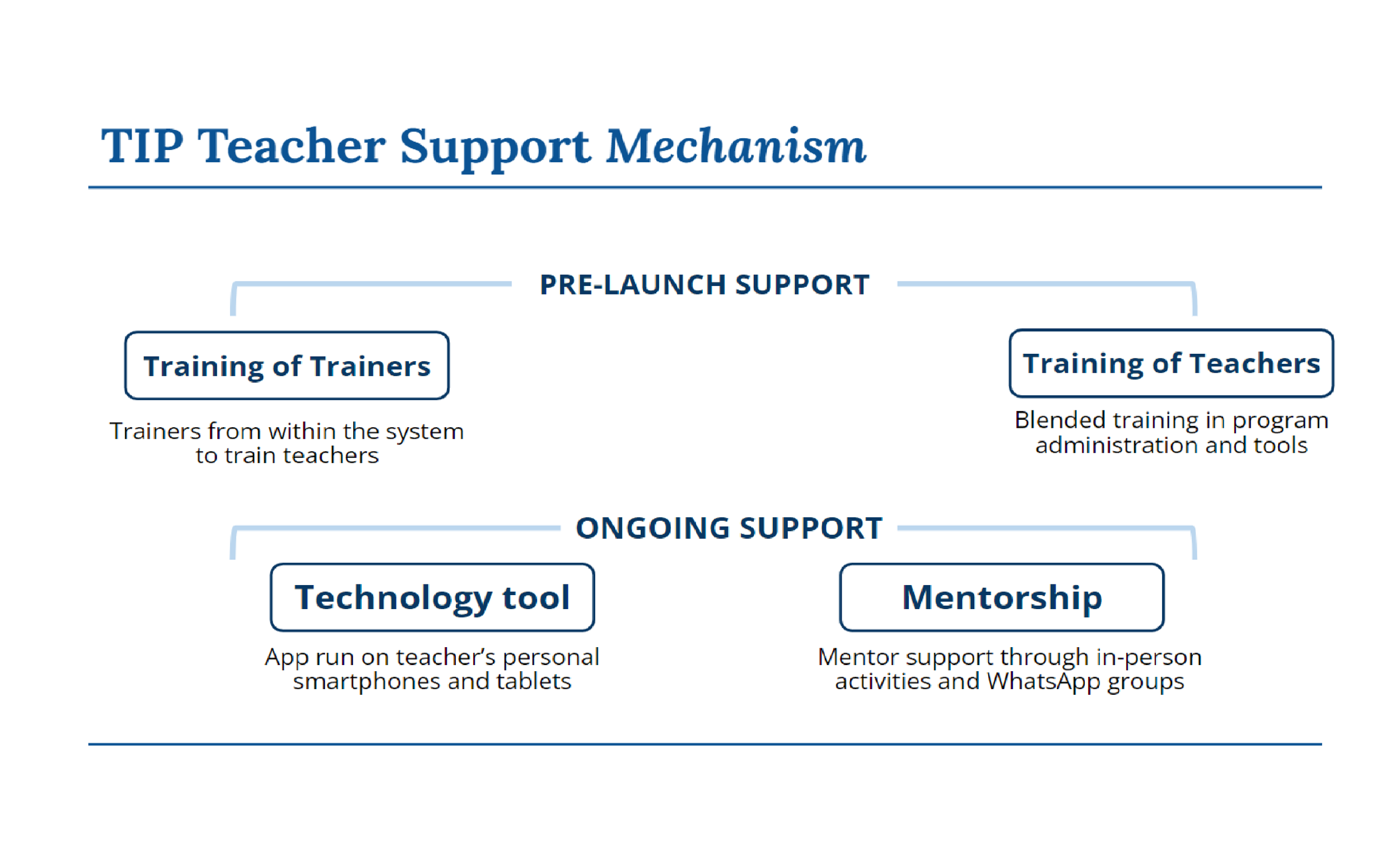

Ecosystem of Teacher Support

TIP trains teachers pre-launch so they are fully equipped with tools and information for implementation. During the program, teachers also receive ongoing support from TIP’s mentors and the technology tool (for treatment schools).

Teacher Support Tech Tool Reduces Teachers’ Administrative Burden

The smartphone application serves as a digital toolkit for teachers, which contains teaching materials, training materials, a digital grading tool, pre-made assessments, a monitoring dashboard, and more. It was created through an iterative process with curriculum experts and teachers, and was reviewed and approved by the Ministry of Education.

Heterogeneity in Teachers’ Traits: Demographics, Beliefs about Pedagogy, and Confidence in Technology

In our sample, teachers display considerable heterogeneity not only in their demographics, but also in their preferences and beliefs towards classroom teaching behavior, adoption of pedagogical innovation, and capability in adoption of technology. Some of this heterogeneity is observable, while some is unobservable (e.g. teachers know their own type better). As such, we aim to study any potential mediating effects on program outcomes due to the observable heterogeneity in teachers’ traits.

Though the average teacher is 40 years old, the strong bimodal distribution in teachers’ age suggests two distinct age groups: young teachers (<35 years old) and older teachers (50+ years old).

There has been a hiring surge in the past decade. Nearly a quarter of all teachers (25%) were hired between 2016-2017 alone, and more than half of all teachers (56%) were hired post-2010.

The highest education level of newly minted teachers at time of first appointment rose steadily over the years. From nearly none in 1980 to 83% in 2018, the proportion of newly hired teachers with master’s degrees increased on average 2.0% per year.

Before 2010, less than half of new teachers (40%) had a master’s degree, but having an advanced degree became the norm for new teachers hired post-2010 (80%).

It is also noteworthy that nearly none of the new teachers hired before 2010 had STEM degrees, while more than a third of those hired post-2010 did. This suggests that newly hired teachers are more technically and empirically capable by training, and are perhaps more open to adopting technological and pedagogical innovation.

We asked teachers to rate their confidence levels across a variety of technology devices (e.g., smartphone, camera, computer, tablet) and digital applications (social media, e-mail, web browser, SMS). Most teachers (68%) are confident using a smartphone, and an even higher proportion are confident using common communication apps like SMS (72%) and WhatsApp (74%).

How do teachers’ confidence in technology change with age or gender?

Younger teachers (hired post-2010) are significantly more confident in using technology applications than older teachers (hired post-2010) do, controlling for other demographic traits.

While male teachers are more confident than female teachers in using smartphones, tablets, computers, and Email, female teachers are more confident in SMS and are also 11% more likely in using it to communicate with parents.

In low-income countries, low average learning and high learning inequality will worsen with COVID-19-related school closures (Azevedo, 2020; Kaffenberger, 2020). The variation in parental capability to facilitate learning from home will exacerbate “within the classroom” learning inequality. Teachers will find it difficult to keep all the children in a post-COVID classroom to learn at the same pace, leading many to fall permanently behind with long-term implications for their education and life outcomes (Andrabi et al., 2020).

One of the most promising solutions to this crisis is through targeted instruction (TI), where content is tailored to children’s actual learning levels rather than their age or grade. TI helps fill in critical learning gaps in basic literacy and numeracy that hold students back and are often not addressed in the age-appropriate curriculum. Driven by innovation and evidence from the Teaching at the Right Level program in India, TI has expanded to countries around the world, and studies suggest learning gains can be dramatic (e.g. Banerjee et al 2016).

The Targeted Instruction Pakistan (TIP) program leverages best practices and evidence about TI from around the world, but adapts the program for the specific context of public schools in Pakistan. The program is administered by regular school teachers during the regular school day, avoiding the need for costly additional teaching resources. For part of the day, primary school children (classes 1-5) are sorted into peer learning groups based on their actual learning levels, rather than by their age. Teachers can then deliver content aimed at filling in learning gaps in three critical subjects: math, Urdu, and English. The goal is to get all students caught up to grade level so they can continue their learning journey under the regular curriculum.

The TIP program also seeks to test a) whether low-cost, simple technology can support teachers in implementing TI at scale in Pakistan; b) the extent of variation across teachers in the costs and benefits of this technology and how that impacts take-up; and c) how the perceptions of technology benefits change with experience. Through an iterative process with experts and teachers, we developed an accelerated curriculum and a teacher support toolkit consisting of teaching materials, a technology-based grading tool, and additional training resources.

A large-scale pilot is currently underway to evaluate the program in two provinces in KP: Peshawar and Mardan. For the pilot, 204,410 students from 1,229 public primary schools were tested to assess their actual learning levels in math, Urdu (the national language), and English.

Key findings from our baseline student testing in May 2022 include:

Students on average have fallen behind, and remediation is desperately needed. More than half of students from every class and subject combination showed need for remediation in foundational skills. In some cases, more than 90% of students in a class showed need for remediation in a certain subject.

The need for remediation is strongest in English, followed closely by math. Performance was strongest in Urdu, however 51-84% of students in each class still required remediation in Urdu.

Students show the highest learning gains in Class 5, however many children are completing primary school without key foundational skills. At the end of their time in primary school, 46% of class 5 students cannot write simple Urdu sentences and 79% cannot write simple English sentences. 19% cannot do addition with carrying, and 75% cannot do subtraction with borrowing.

Girls and students from Urban areas show slightly less need for remediation than boys and students from rural areas, particularly in English and Urdu. This difference increases in classes 4 and 5. Performance across Mardan and Peshawar provinces is similar.

These findings highlight the need for programs like TIP to get children caught up. By investing now in filling key learning gaps, children will be ready to continue their learning journey through primary school and beyond.

Meet the Team

-

Tahir Andrabi

PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR, POMONA COLLEGE

-

Juan Baron

PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR, WORLD BANK

-

Isabel MacDonald

PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR, UC BERKELEY

-

Zainab Qureshi

PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR, INDEPENDENT

-

Maleeha Hameed

PROGRAM MANAGER, CERP

-

Angela Tran

RESEARCH FELLOW, HARVARD