Summary: Pakistan ranks in the lowest decile in female labor force participation, and even in sectors where women are more prevalent, such as teaching, they earn 70 cents for each dollar men earn. While we have extensive evidence on the prevalence of gender bias in hiring, promotions and wages, we know less about the mechanisms underlying this bias and the extent to which certain personnel policies may mitigate or exacerbate these biases. To test this, I conduct a large scale field experiment with 3,600 employees in 250 schools and randomly vary i). how often managers observe a given employee and ii). whether manager evaluations affect employee’s pay or are just used for feedback. First, I find when there are no financial stakes associated with performance evaluations, there is no gender bias. This is true both using data from actual performance evaluations, controlling for the aspects of performance I observe, and for randomized vignettes varying the gender of the teacher. In contrast, when principals’ evaluations determine teachers’ end of year raise, we see that female teachers receive 10% lower raises, controlling for productivity. However, when principals are randomly assigned to conduct more frequent classroom observations of teachers, this lowers their evaluations of male teachers and results in gender parity in evaluation scores even under financial stakes. Combined this suggests that improving the accuracy of manager information could close the gender gap in performance evaluations, even in high stakes settings.

Understanding Gender Discrimination by Managers

Citation: Brown, Christina. 2022. “Understanding Gender Discrimination by Managers”, Working Paper.

Christina Brown

Across the world, women earn half what men earn. This enormous gap in earnings is due to differences in labor force participation, wages and hours, and is significantly worse in many parts of the world. In Pakistan, the setting for this study, men are more than three times as likely to work as women, ranking in the bottom decile for female labor force participation. Even in sectors where women are more prevalent, such as teaching, women earn 70 cents for each dollar men earn. One contributing factor to these gaps is likely the extent of gender bias throughout the personnel process–hiring, promotions, raises, firing, etc, which has been shown to be endemic.

In addition to concerns about equity, there are also wider productivity consequences of the biased nature of personnel policies. Because many firms and governments worry about biased performance evaluation systems, employees, especially in the public sector, are subject to little to no performance incentives. While we have overwhelming evidence on the prevalence of gender bias throughout the labor market in many settings, we have less understanding about why these disparate outcomes occur and the extent to which other personnel policies amplify or mitigate bias.

In this paper, I use a large-scale experiment with 200 managers and 3,600 teachers across 250 schools in Pakistan to vary features of the personnel system to test the conditions under which gender bias exists and better understand how well-designed HR systems can constrain manager bias. First, I vary whether managers’ performance evaluations of employees determine the employee’s end of year raise or if they are solely used for feedback. Second, I vary how often managers are required to conduct classroom observations for certain teachers. I then measure teacher productivity in detail, including value-added, daily attendance, time use and measures of pedagogy from classroom observation videos.

Study Design and Findings

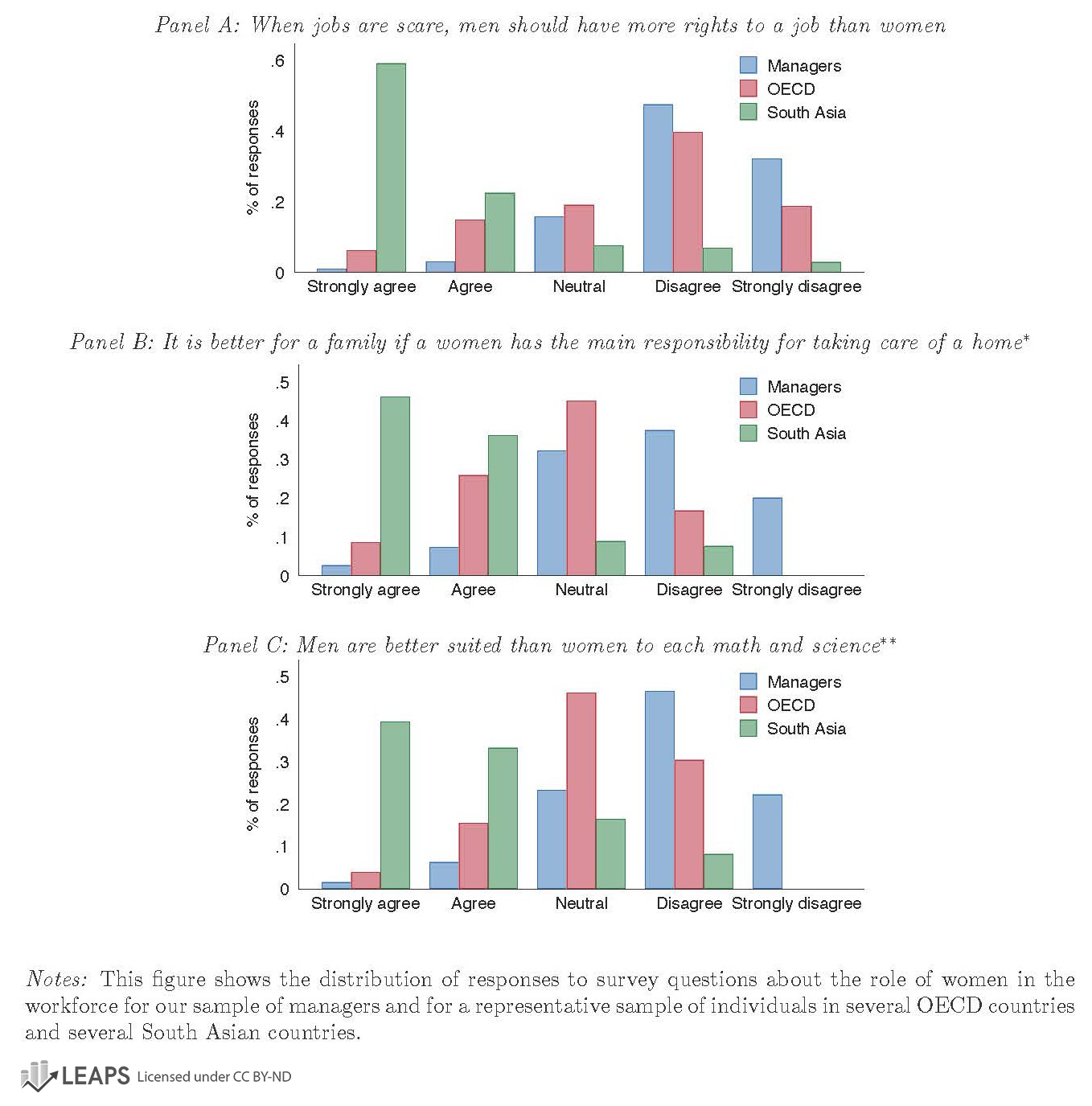

Managers in the sample do not have an overt bias against female teachers

First, I show that our sample of managers have relatively minimal overt or taste-based discrimination against female teachers in all three bias measures we conduct. Our managers have significantly more progressive views of women in the workplace than a representative sample of adults in OECD countries. We also do not see any bias when managers are asked to provide sample evaluation scores for example teachers based on a short vignette, where we randomly vary the gender of the teacher in the vignette. Lastly, when we ask teachers about the extent of bias toward or against certain groups, teachers do not believe there is discrimination against or in favor of female teachers.

Low stakes evaluations have no gender differences, while high stakes evaluations do

I find that when evaluation scores have no financial stakes for employees, male and female teachers receive nearly identical evaluation scores, controlling for teacher productivity. However, when the evaluation score determines the employee’s raise, men receive a 10% higher raise than women. This result holds for both male and female managers.

Providing information to managers reduces the gender evaluation gap

Finally, I find that better information helps to close the gender evaluation gap. When managers are required to observe certain teacher’s classrooms more frequently, I find this makes them much better able to predict teachers performance on a number of dimensions. Then in turn, I also find that male and female teachers who were observed more frequently receive nearly identical evaluation scores. Whereas, for teachers who were observed less frequently, I find male teachers receive 12% higher raises conditional on the employee’s quality. I also find suggestive evidence that the observation treatment is able to mitigate the negative effects of financial stakes, reducing their effects by about two-thirds.

Study Resources

The following resources are for public use in presentations, papers, lectures, and more under the Creative Commons license BY-ND. Click the images below to view or download individual images, or use the button to download all.

As a condition of use, please cite as: Brown, Christina. 2022. “Understanding Gender Discrimination by Managers”, Working Paper.